Hello and welcome!

It’s my aim to use this space to share my experiences as I delve back into the ancient craft of Wet Plate Collodion image making. In order to do so I need to indulge in a bit of retrospective blogging.

About 4 or 5 years ago I was given a small glass photograph. A small piece of glass with a decorative brass edge framing a family portrait of a woman and what I assume to be her six children. I absolutely loved it – in fact I loved it so much it took pride of place in my loft darkroom. I set about trying to find out more about what it was exactly. I have never studied photography, and despite always having a love of shooting black and white film and making fibre prints, I realised that I knew absolutely nothing about what came before the so super convenient rolls of film I eat up every day.

Now my darkroom is not a conventional space – don’t get me wrong I love it and I don’t think I could improve upon it – but my large format enlarger only just fits between the rafters and on raising the head of it one day it whacked the rafter setting in motion a chain of events which resulted in the plate falling from it’s vantage point onto my easel. It was broken 🙁

Thankfully the decorative edging held the glass together but, as you can see, it’s badly cracked.

At the same time I was discovering that this glass photo was in fact a Black Glass Ambrotype (BGA), and that the image was actually a negative which appeared as a positive due to the black backing, and a slightly different chemical treatment when making the emulsion and developing it.

I also discovered that the same image could have been made on black metal, in which case it would have been a Tintype, and not even I could have broken that……could I……… 🙂

Broken or not this little glass plate fascinated me so much that I felt compelled to discover more about the wet plate collodion process. In doing so I was absolutely amazed by some of the historical work I found.

My initial research was really just out of curiosity. It was such an involved and problematic process it amazed me that any images were ever made at all, and it is incredible that so many, especially the glass ones, exist today.

I’m a carpenter to trade and I was firstly drawn to the unique hand made qualities of the plates I was able to see. Looking past these artisan trademarks I was further drawn into the images themselves. The steely concentration of the subjects as they held poses to burn their image into the wet collodion. I loved it – and I had to find out how to do it. I wanted to try it myself.

For almost four years I investigated further, looking for pieces to an unknown jigsaw which only in the past 12-18 months have started to come together. I really wanted to work with authentic period equipment which initially proved to be very frustrating. Late 1800’s cameras are not easy to come by and a lot of people who own them are collectors who start to foam at the mouth at the suggestion of actually putting them to use. Furthermore, the price tags which accompany a lot of good period equipment, particularly lenses, were above my humble reach.

I eventually managed to find a broken Kodak 2D 10×8 field camera, somewhere in the American mid West, which came with a lovely brass Wollensak f5.6 Portrait Lens. I repaired the camera without much trouble and a friend machined an alloy flange for the lens, however, it was so big and heavy I had to fit it to a steel lens board and finish the steel with a cherry veneer. I also made a cherry lens cover with a copper rim. Exposure times tend to be in the seconds so the lens cover doubles as the shutter : – ))

As my search for equipment progressed my application for 190 proof alcohol was approved and the world seemed like a better place 🙂 – how did they focus?…. hic! (joking aside it ain’t for drinking)

Slowly but surely things came together and I was able to have a go at making my first portraits: –

Later that year I managed to coax my two sons out of the paddling pool for a portrait: –

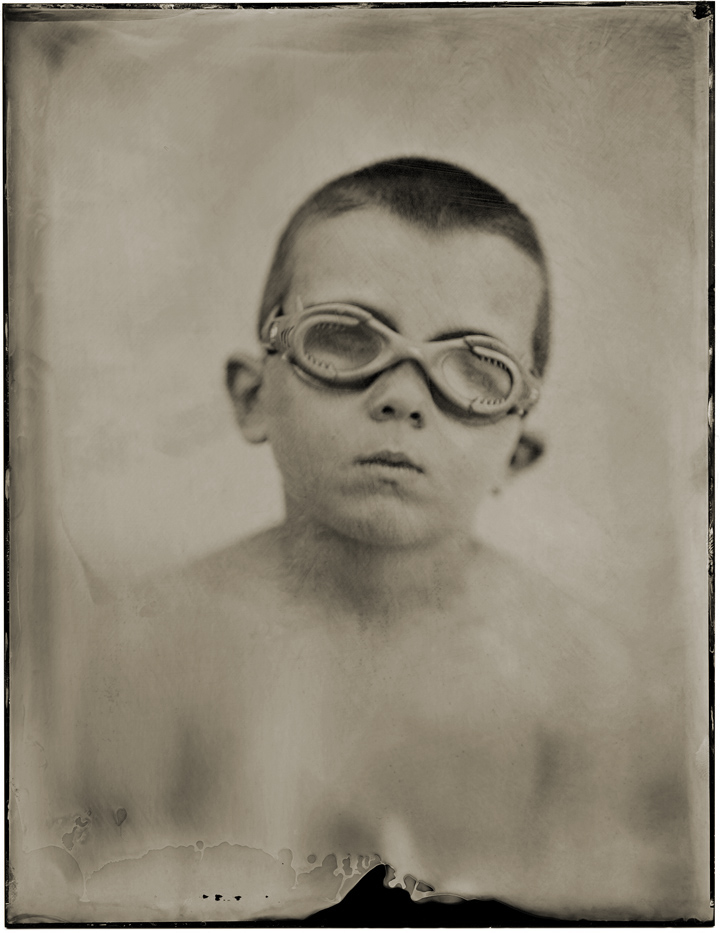

Cameron Jack Gillanders, aged 7: –

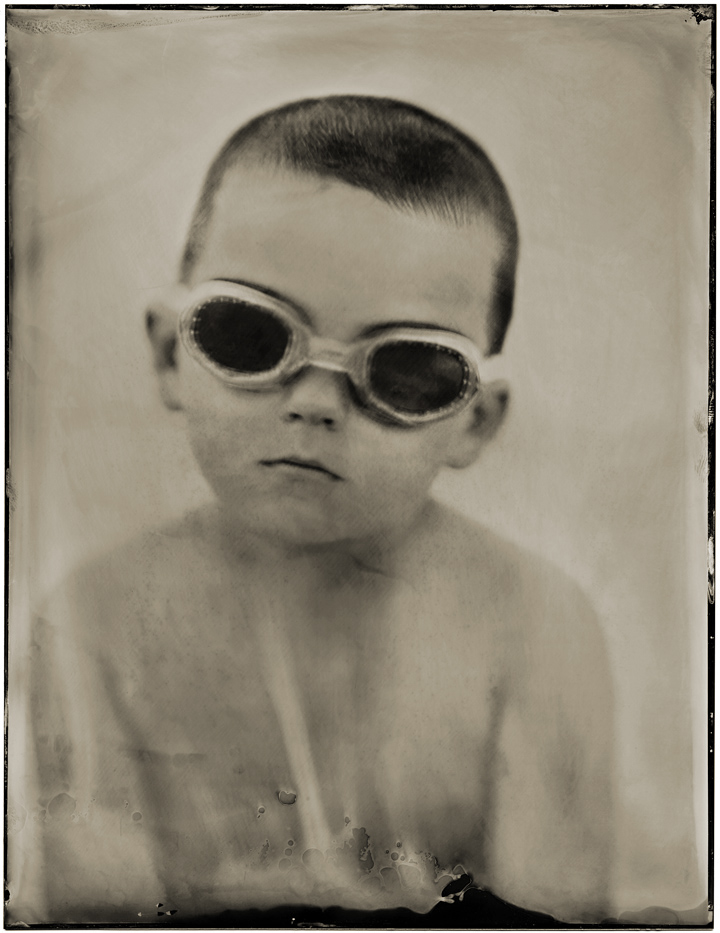

Brodie Mac Gillanders, aged 5: –

I was hooked – I loved the hands on process, the smells, the defects and most of all I loved the way the subject is forced to really participate and engage with the camera.

I made all of these plates in my back garden running from the camera up into my loft darkroom to prepare the plates and develop them, but I wanted to be able to take this out on the road – how could I do it? I needed a portable darkroom which I made out of a tent for growing weed and a few rolls of gaffer tape. I know it’s a strange picture – and it only gets stranger 🙂

I took my mobile madness up to my friend Jim Fairlie’s farm in Perthshire where he and his farm hands watched on in amazement as I took over his front room with weed tents, 190 pure alcohol and all sorts of smelly chemistry to make the following plates: –

Jim Fairlie: –

Mike: –

Mark: –

The guy who was fixing Jims roof: –

Now weed tents are, I’m sure, great for growing weed but they proved to be a bit time consuming to erect and given the wind we get in Scotland I knew I couldn’t rely on it for outside use. I was lucky to have Jim’s understanding to put it up in his house, and I’m sure he’s worked round the silver nitrate stains on the carpet – and the mantlepiece. Right Jim?

I needed something more substantial for this work – but I’ll leave that for the next post.